[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text dp_text_size=”size-4″]The audience at Edith Kanaka’ole Stadium in Hilo, Hawai’i, was engulfed in silence as a group of hula dancers took the stage. Their graceful and synchronized movements beautifully depicted an ancient Hawaiian myth while their melodic chants resonated through the air. This mesmerizing hula performance was not just a spectacle; it represented a profound celebration of Hawaiian culture, a celebration that had been prohibited for many years.

The Merrie Monarch Festival, which recently marked its 60th anniversary, is often hailed as the “Olympics of hula.” It serves as a week-long event that not only showcases the art of hula dancing but also serves as a crucial means of preserving and sharing the native Hawaiian language, history, religion, and culture. Thousands of Hawaiians gather on the Big Island to attend the festival, while many more around the world tune in to watch the live broadcasts of the competitions featuring Hawai’i’s top hālau (hula groups). Beyond being a hula contest, the festival encompasses dance performances, arts and crafts exhibitions, and a grand parade through downtown Hilo, making it the largest showcase of Hawaiian culture globally.

According to Kū Kahakalau, a Hawaiian language and culture expert, the Merrie Monarch Festival is a cherished annual occasion that allows Hawaiians to come together and celebrate their heritage. It owes its existence to the efforts of King Kalākaua, who played a significant role in revitalizing and promoting Hawaiian cultural practices.

Often referred to as “The Merrie Monarch,” King David La’amea Kalākaua was the last ruler of Hawai’i. From 1874 until his death in 1891, he governed the Kingdom of Hawai’i amidst a tumultuous path to the throne. Following the passing of King Kamehameha IV, who had ruled the kingdom for almost a century, the Hawaiian legislature controversially decided to elect a native ali’i instead of the late king’s widow. This decision sparked a violent riot, with supporters of the queen storming the Honolulu courthouse. The ensuing chaos required the intervention of British and American sailors stationed at Honolulu harbor to restore order, ultimately leading to Kalākaua assuming the throne.

Also Read: The most anticipated museum in the United States finally opens.

During Kalākaua’s reign, the Native Hawaiian heritage faced significant threats. The arrival of Christian missionaries in 1820 had devastating consequences, bringing diseases that decimated the Native Hawaiian population, introducing a new religion that replaced traditional beliefs, and imposing restrictions on cultural practices. One of the most notable prohibitions was the ban on public performances of the hula, which the missionaries regarded as heathen and immoral.

Kalākaua aimed to rejuvenate a sense of national pride among the Hawaiian people and initiated a cultural renaissance throughout the islands. Guided by his motto, Ho’oulu Lāhui (Increase the Nation), he sought to revitalize Hawai’i for Hawaiians, leading to the revival of traditional customs, including language, music, arts, and traditional medicine, which had been suppressed during the era of his predecessors influenced by missionaries. Preserving the hula was one of his significant accomplishments. As Kalākaua eloquently stated, “Hula is the language of the heart, and therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people.”

While many may associate “hula” with commercialized and misrepresented depictions, such as those seen in tiki bars or tourist resorts, the dance has a much deeper significance to Native Hawaiians. Long before it was commodified, the hula held sacred importance as an ancient practice, serving as a repository of stories, beliefs, and ways of life. Before the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778, Hawai’i had no written language, relying instead on oral traditions and hula to transmit their identity and culture from one generation to the next. Even during the period of prohibition, Hawaiians clandestinely continued to pass on the forbidden dance, teaching it in secret locations such as caves and remote areas.

Under Kalākaua’s Ho’oulu Lāhui policy, the hula underwent a notable revival. The king’s extravagant two-week coronation ceremony became a vibrant tribute to Native Hawaiian culture, incorporating traditional music, hula performances, and festive lū’au feasts that were previously prohibited. Three years later, on his 50th birthday, ho’opa’a chanters and ‘ōlapa dancers took to the public stage once again, accompanied by a lively parade through downtown Honolulu. Today, the Merrie Monarch Festival stands as a testament to the resolute pride in Hawaiian heritage that Kalākaua rekindled.

According to Kahakalau, “[Kalākaua] possessed a deep commitment, sense of pride, and profound knowledge of his Hawaiian ancestry,” highlighting his pioneering achievement of having the Kumulipo, a creation chant intertwined with the genealogy of Hawaiian royalty, transcribed.

However, Kalākaua’s aspirations extended beyond the revitalization of Hawaiian customs within the islands; he aimed to share the Kingdom’s culture with the world. Thus, in 1881, the “Merrie Monarch” embarked on a remarkable journey, embodying the enduring Hawaiian tradition of seafaring by circumnavigating the globe for 281 days, becoming the first head of state to achieve this feat.

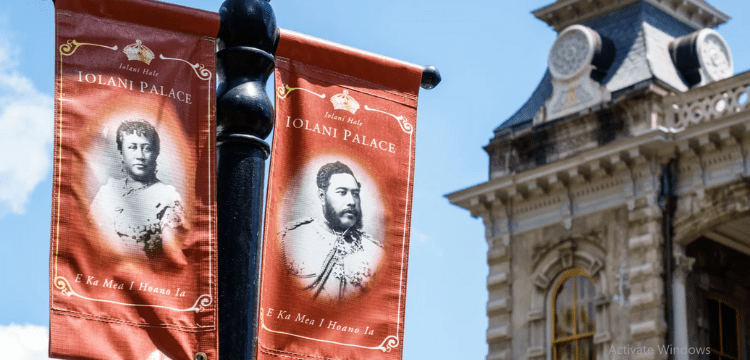

During Kalākaua’s international diplomacy tour, he received a warm welcome from the Emperor of Japan with the sounds of Hawai’i Pono’ī, the Kingdom’s national anthem composed by Kalākaua himself. He engaged in discussions on immigration policies with Chinese politicians, explored the Great Sphinx alongside the Khedive of Egypt, received a blessing from Pope Leo XIII in Rome, shared tea with Queen Victoria of England, and even encountered a train collision with a bull in Spain. In New York, Kalākaua met with Thomas Edison to explore the possibility of bringing electricity to Honolulu. In 1886, his wish became a reality when ‘Iolani Palace, now a museum and the sole royal residence in the United States, became illuminated with electric lights, preceding the White House’s adoption of electric lighting by five years.

“He had the capacity to form important relationships, forge connections, and sign agreements with multiple nations that brought advantages to our community,” stated Kenneth “Aloha” Victor, a master hula teacher and the founder of Kaulua’e, a Hawaiian clothing and lifestyle brand. Alongside dispatching envoys to Europe and Asia, Kalākaua maintained consulates and diplomatic missions in over 130 cities worldwide, including 13 consulates in Great Britain alone.

On the domestic front, during a time of increasing literacy, Kalākaua convened with traditional priests and elders to document numerous ancient Hawaiian legends and chants, which are showcased through hula and mele (songs), and transcribed them in the Hawaiian language. In 1888, he went a step further and translated these narratives into English for the first time in the book “Legends and Myths of Hawai’i,” often presenting it as a gift to foreign dignitaries to provide them with a deeper understanding of Hawai’i, its culture, and its people.

Kalākaua’s commitment to integrating Hawai’i into the global community also led to the establishment of the Hawaiian Youths Abroad Program. Through this initiative, the king selected young Hawaiians whom he believed could become future leaders of the Kingdom and sent them overseas to study various disciplines such as medicine, law, engineering, foreign languages, and art. More than a century later, the program’s legacy continues to resonate throughout the islands. Princess Abigail Kawānanakoa, the granddaughter of one of the students sent abroad, played a pivotal role in restoring ‘Iolani Palace and championed the rights of native Hawaiians until her passing in 2022.

Kalākaua was truly a polymath, embracing modernity while valuing Hawaiian culture. He possessed a keen inventiveness, crafting designs for tornado-resistant ships, fish-shaped torpedoes, airtight bottle caps, and rangefinder scopes. He even installed a telephone that connected ‘Iolani Palace, his residence and workspace, to his private boathouse less than a mile away. It was there that he frequently hosted royal lū’aus for foreign dignitaries and heads of state.

Kalākaua’s legacy extends far beyond being a multi-talented individual for Hawaiians today. According to Ana Kon, a Hawaiian cultural specialist, his travels abroad were an opportunity to showcase and disseminate our culture worldwide. This enduring impact is evident in the ongoing reverence for his legacy at the Merrie Monarch Festival.

For those unable to secure tickets to the highly sought-after hula competitions at the festival, there are still numerous ways to participate in the festivities. Hilo’s Afook-Chinen Civic Auditorium and Butler Buildings host a vibrant arts and crafts fair, featuring the work of over 150 local artisans and brands from across Hawai’i. Victor, creator of the Kaulua’e clothing brand, explains that their “aloha wear” celebrates hula and pays tribute to the people, places, and movements of Hawaiian culture.

Beyond the festival, Kalākaua’s influence continues to resonate. Every hula step, lū’au gathering, and Hawaiian-language phrase serves as a testament to his efforts to revive our customs locally and introduce them to the world. Visitors can personally experience this cultural legacy at O’ahu’s Polynesian Cultural Center, where a traditional Hawaiian lū’au pays homage to Queen Lili’uokalani (Kalākaua’s sister and his successor until the Kingdom’s overthrow in 1893). Additionally, the Queen Emma Summer Palace in Honolulu offers contemporary hula lessons for adults, providing an opportunity to engage with this rich heritage.

At the Grand Wailea on Maui, visitors can engage in enriching experiences. They have the opportunity to participate in a morning E Ala E oli (chant) on the beach, immersing themselves in the Hawaiian culture. Additionally, the resort’s A’o Cultural Center at Outrigger Reef in Waikiki Beach embraces a regenerative tourism approach. Guests can interact with traditional Hawaiian navigators and canoe builders, learning about their craft and getting hands-on experience with traditional Hawaiian tools. As part of these experiences, visitors can also take part in hula lessons, connecting with the vibrant tradition of Hawaiian dance.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]